Letter reversals, particularly confusion between b and d, are one of the most common challenges that emerge as children learn to read and write. Parents and educators often notice reversals during early writing tasks and wonder whether the child is struggling, guessing, or falling behind.

In reality, letter reversals are a predictable part of development. They reflect how the brain initially processes visual symbols, not a lack of effort or intelligence.

This guide explains why letter reversals happen, what is developmentally typical, and how to address reversals through effective handwriting instruction and targeted support that strengthens both writing and reading. The strategies here align with the same foundations emphasized in research-based letter formation instruction, where starting points, stroke direction, and efficient motor patterns are taught explicitly.

Why Letter Reversals Happen

Mirror Invariance and the Developing Brain

The area of the brain that eventually specializes in letter recognition originally evolved to recognize faces and objects. This system is designed to identify objects as the same regardless of orientation.

A pencil is still recognized as a pencil whether it is upright, upside down, or turned sideways.

This ability, known as mirror invariance, is helpful in daily life but works against children when they are learning letters. Early on, the brain naturally treats letters such as b, d, p, and q as variations of the same shape. Over time, instruction and practice help the brain learn that orientation matters for written language.

With instruction and practice, children gradually learn to override mirror invariance by strengthening the connection between:

- what they see

- what they hear

- how they move

That process takes time, and it is highly dependent on how letters are taught.

What Is Typical and When to Be Concerned

- Letter reversals are common up to age 7, and sometimes even 8.

- Reversals are especially common in left-handed children.

- Reversals alone are not a sign of dyslexia.

- Concern increases when reversals persist beyond second grade and interfere with reading, spelling, or writing fluency.

The goal of intervention is not eliminating reversals in isolation. The goal is improving functional reading and writing.

How to Fix Letter Reversals Instructionally

The Key Role of Letter Formation

The most effective way to reduce letter reversals is through consistent, efficient letter formation. When children know where a letter starts, the direction it moves, and how it feels to write, the brain develops a stable motor plan.

As letter formation becomes automatic, reversals naturally decrease. Targeted, correct practice matters far more than the number of repetitions.

This approach fits naturally within science-of-reading aligned handwriting instruction, where letter formation, sound–symbol mapping, and motor memory work together to support fluent decoding and spelling.

Teach Confusable Letters Separately

Letters such as b and d should not be taught together or within the same letter group. Instead, each letter should be introduced in a different letter family.

Teaching b first, followed later by d, allows the brain to store each movement pattern independently. When letters are introduced simultaneously, students are required to compare and discriminate before either letter is learned, which increases confusion and reliance on visual guessing.

Once both letters are taught, they can then be intentionally paired for comparison and discrimination practice. At that point, the contrast becomes meaningful rather than overwhelming.

Address Underlying Skills That Contribute to Reversals

Laterality and Directionality in Letter Reversals

Children who experience frequent letter reversals often also have difficulty with left–right directionality. Before a child can consistently discriminate between b and d, they need a clear internal sense of:

- left versus right

- where writing starts

- how movement flows across the page

Directionality develops first through body awareness, then transfers to hand movements, and finally to written symbols. When this foundation is weak, reversals are more likely to persist even with repeated visual practice.

Activities That Support Directionality

The following activities support laterality, spatial awareness, and directional control, which directly impact letter reversals.

Body-Based Directional Awareness

- Play Simon Says using left and right commands (for example: “Touch your right foot,” “Raise your left hand”).

- Have the child follow directions involving body movement and position.

Visual–Motor Directionality

- Draw lines up and down, left to right, and across the midline.

- Connect dots to complete a pattern in a left-to-right sequence.

Sequencing Skills

- Arrange story pictures in left-to-right order.

- Talk through what comes first, next, and last.

Writing Supports

- Use lined paper consistently to reinforce spatial boundaries.

- Use a weighted wristband to help designate right versus left hand when needed.

These activities strengthen the same directional systems children rely on when distinguishing letters.

Cognitive Strategies That Support Letter Discrimination

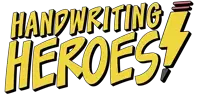

Focus on Starting Points

Before students write b or d, prompt them to answer one critical question:

“Where does this letter start?”

Instead of answering verbally, students respond with a quick body movement. This shifts the task from visual guessing to recalling the correct starting position and movement pattern.

- For b: Students reach both arms up toward the sky. This reinforces that b starts at the top line and moves straight down before the curve is added.

- For d: Students move both arms out to one side in a curved shape. This reinforces that d starts at the midline (the clouds) and begins with a curved motion.

This brief movement cue anchors the letter’s starting point in space before the pencil touches the paper. It also encourages use of the helping hand and strengthens motor memory.

You can also turn this into a simple movement sequence or “dance.” Call out a pattern such as b, d, d, b, and have students perform the matching arm movements in order. It can also be embedded into a Simon Says activity so students must listen carefully, respond with the correct movement, and then write the letter.

Over time, students internalize these starting-point cues and no longer need the physical movement. As the motor plan becomes automatic, the body cue fades and accurate letter formation takes its place.

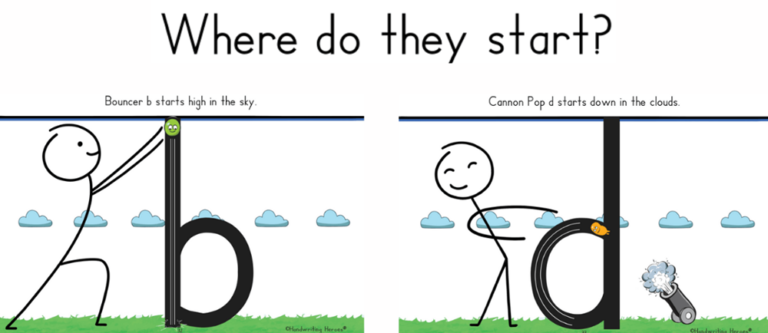

Hand Cues for Distinguishing b and d

Hand cues provide a physical reference for letter orientation that helps students distinguish between visually similar letters such as b and d. Because left–right directionality is still developing in many young children, relying on visual memory alone often leads to guessing.

A commonly used strategy is the “bed” hand cue, where students hold up both hands to form the letters b and d. While this can be helpful initially, using both hands at once can increase cognitive load and slow decision-making during writing.

A more effective approach is to reduce the cue to a single hand.

For right-handed students, the left hand, non-writing hand, forms the letter b. The straight thumb represents the vertical line, and the curved fingers represent the circle. For left-handed students, this cue can be mirrored using the right hand. This creates a consistent spatial anchor that supports orientation without requiring comparison between two options.

Instructionally, the hand cue should be introduced alongside letter formation, not as a separate memory trick. Before writing, the teacher can prompt the student to briefly check the hand cue, identify the correct starting stroke, and then immediately write the letter using the correct movement pattern.

Over time, the goal is for students to rely less on the hand cue and more on their internalized motor plan. As letter formation becomes automatic, the need for external cues naturally fades.

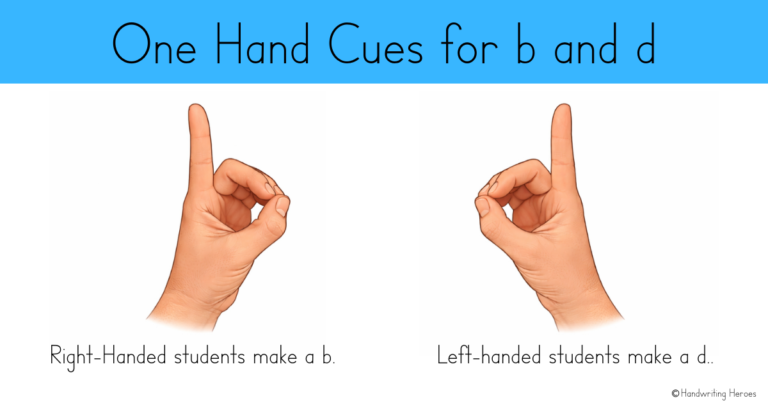

While hand cues anchor where the letter starts and which direction it faces, mouth formation reinforces how the letter connects to sound.

Using Mouth Formation to Reinforce Letter Orientation

Mouth formation provides an additional sensory cue that links speech production directly to letter formation. When students attend to how their lips are positioned before producing a sound, they gain information about which letter they are about to write.

- /b/: lips begin closed, which mirrors the straight line that starts the letter b

- /d/: lips begin open and rounded, which mirrors the circle that starts the letter d

Explicitly pointing out this parallel helps students connect sound, movement, and letter shape, reducing reliance on guessing.

Letter-Specific Teaching Strategies

For d

- Say: a, b, c.

- Have the student write a c.

- After c comes d! Continue the motion to finish the letter.

For b

- Use the cue that the stick comes first, then it hits the ball.

- Emphasize the vertical line before the circle.

Optional memory supports may include:

- b for bacon, d for donuts

- b for belly dancer, d for diaper

Clear movement patterns support motor memory and reduce reversals.

Supporting Self-Correction

Students need tools that help them notice errors before they repeat them. Effective supports include:

- A visible starting dot at the beginning of the letter.

- Letter strips for reference.

- Consistent visual anchors on the page, such as placing a model b on the top left and d on the top right, provide a constant orientation reference.

Self-monitoring reduces the chance that incorrect patterns compete with correct ones, helps students rely less on adult prompts, and strengthens accurate motor patterns over time.

Increase Exposure With Purpose

Instead of avoiding confusing letters, increase meaningful exposure:

- Letter-sound drills

- Dictation

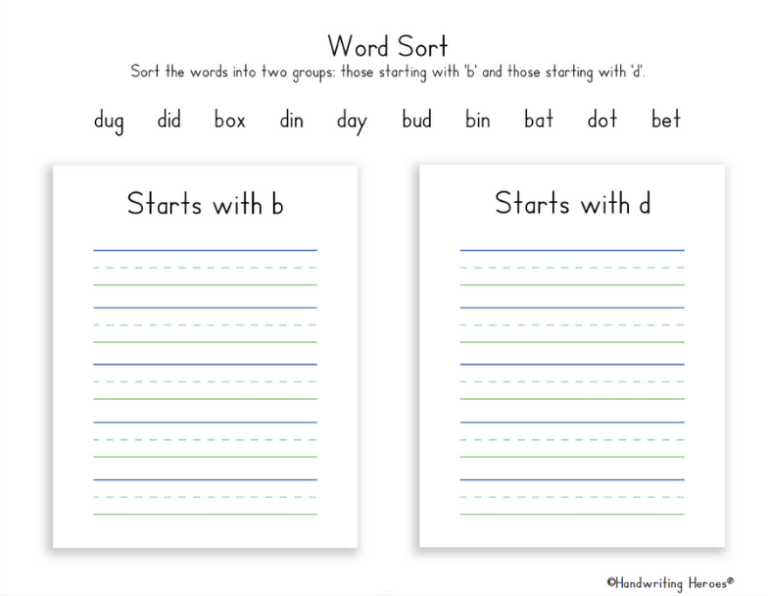

- Word sorts for b words and d words

- CVC words emphasizing initial sounds

Plan explicit conversations about why these letters are easy to mix up and what helps the brain choose correctly.

When to Look Deeper

In some cases, letter reversals reflect broader difficulty with phonetic decoding rather than a handwriting issue alone. This is more likely when reversals persist beyond the expected developmental window and noticeably affect reading progress.

- Examine phonetic decoding skills.

- Consider phonological processing.

- Account for bilingualism, language exposure, and cultural context.

Because reversals often show up alongside other early literacy needs, it can help to keep handwriting practice connected to real reading and writing tasks, especially in classrooms where screen-based work is common. Many educators also notice improved focus and persistence when pencil-and-paper routines remain part of daily instruction, a theme explored in why handwriting still matters in the digital age.

The goal of intervention is improved reading fluency and efficiency, not compensatory strategies.

Final Thoughts

Letter reversals are not a flaw. They are part of learning how written language works.

The most effective intervention focuses on efficient letter formation, strong directionality, consistent practice, and precise feedback. When students are anchored in movement, sound, and spatial orientation, the brain stops treating letters as interchangeable shapes and begins treating them as meaningful symbols.

That is when reversals fade and fluent reading and writing take their place.