There is a widely held perception that uppercase letters should be taught first because they are easier to write. This is commonly accepted as a fact. However, in order to provide the best instructional outcomes for our students, it is imperative to critically examine this assumption.

Are Uppercase Letters Easier to Write?

1. Starting Points

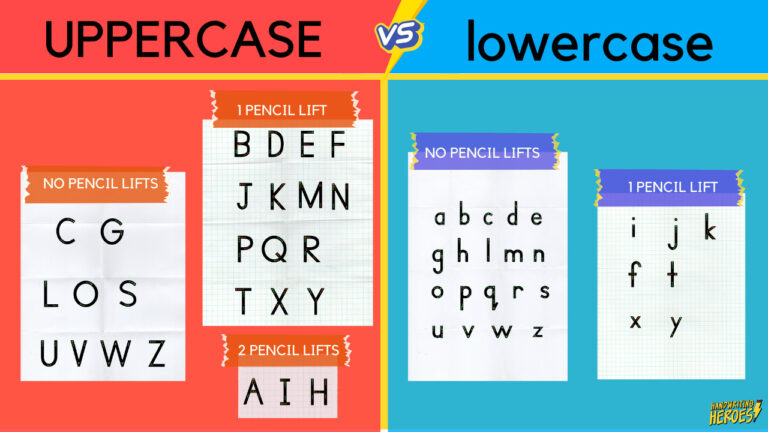

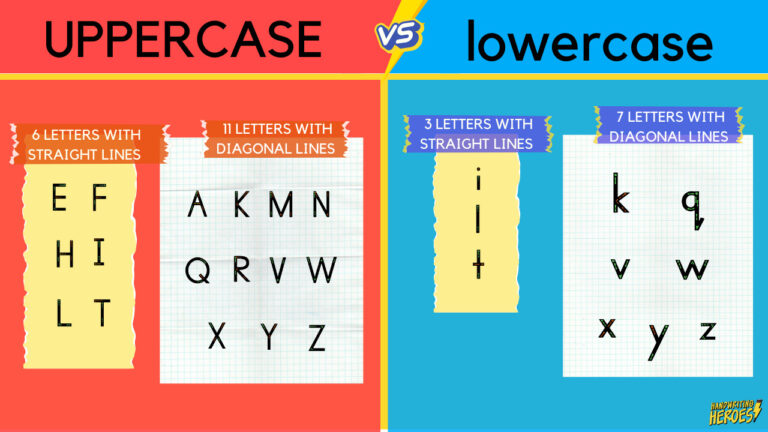

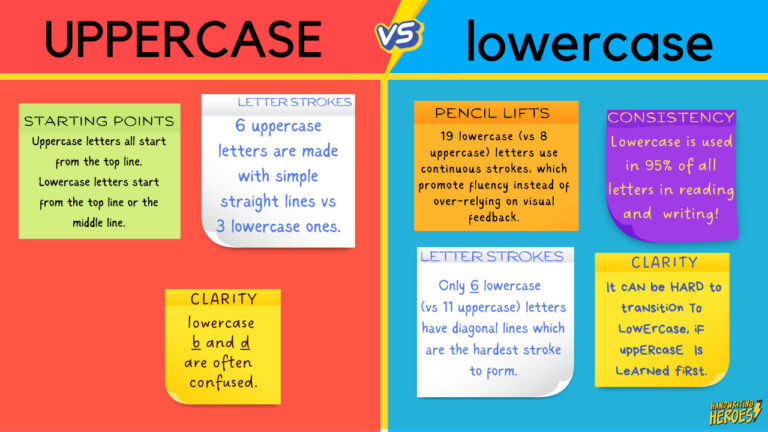

Having fewer starting points simplifies the decision on where to start. All the capital letters start at the top line whereas lower case letters can start at the top line or at the midline. This factor favors uppercase as being easier to learn.

2. Pencil lifts

When you write, picking up the pencil and putting it down again needs careful visual monitoring and precise motor skills to neatly place the pencil at the start of the next stroke. Seventeen uppercase letters need two or more lifts, compared to only seven lowercase letters. Take the uppercase “A,” for example, with its three distinct strokes, necessitating a lift and precise placement of the pencil at each transition point, relying heavily on visual guidance. In contrast, lowercase “a” is formed using one smooth, continuous stroke, that is not constrained by accuracy demands. This suggests that lowercase letters are easier and more efficient to form.

3. Letter Strokes

Letters are created by combining two or more basic strokes. These strokes are typically learned in a specific developmental order: vertical lines, horizontal lines, circles, and finally diagonal lines. Accordingly, letters with vertical and horizontal lines are easier to write. Given that there are six uppercase letters that are composed of these straight lines versus three lowercase letters, it would be easy to conclude that uppercase has an advantage. That is, until one considers the diagonal line – which is known to be the most complex stroke used in letter formation. Eleven uppercase letters contain diagonal lines in contrast to seven lowercase ones.

Overall, while some aspects may favor uppercase letters, such as starting points, others, like the infrequent need for pencil lifts, may tip the scale in favor of lowercase letters. Considering these factors, it becomes apparent that the ease of writing uppercase versus lowercase letters is not a clear-cut matter. Therefore, instead of presuming inherent advantages of uppercase letters, we should adopt the perspective that both upper and lowercase letters are equally manageable to form. Our attention should then pivot towards identifying what proves most effective in practical use.

Aligning Handwriting with Reading and Writing

The majority of words students read and write are in lowercase, constituting approximately 95% of all characters in typical texts. Mastering lowercase first not only facilitates accurate writing sooner but also supports reading development.

Some lowercase letters like b, d, p, g, q, share visual similarities, potentially causing confusion. By aligning handwriting instruction with reading, educator’s can significantly improve students’ capacity to differentiate these visually similar letters. This approach is particularly advantageous for kinesthetic learners, as it integrates the physical act of writing with the visual process of identifying the letter.

Additionally, lowercase words are generally easier to read, thanks to the distinct shapes formed by ascenders and descenders. In contrast, uppercase letters are likened to “big rectangular blocks,” taking longer to process, as Jason Santa Maria explains in his article, “How We Read.”

Transitioning from Upper to Lower Case

Students who initially focus on learning uppercase letters may encounter challenges when shifting to lowercase. Repetitive practice of uppercase letters strengthens neural pathways in the brain, automating the process of writing in uppercase. Consequently, when students need to use their working memory for the new task of writing in lowercase letters, they instead rely on the well-established neural pathways associated with uppercase forms.

Learning uppercase letters first is akin to using the “hunt and peck” method in typing. Individuals can become adept at finding and pressing keys individually, achieving reasonably good typing speeds. Therefore, it becomes easier for them to default to this method, which is already ingrained in their motor memory, rather than investing the time and effort required to learn correct touch typing. Despite the initial slower production of touch typing, using this method is far more efficient in the long run. Simply put, it’s easier to stick with what one knows than to take on the challenge of learning something new.

What do the experts say?

Expert voices affirm the advantages for lowercase letters. Dave Thompson, CEO of Educational Fontware, and designer of over 900 fonts said, “Lowercase is definitely easier. There are fewer pen lifts, and much more similarity between smalls (a, c, d, e, g, o, q for example all start with or have a counterclockwise hook) than caps. Lowercase uses retrace without pen lift for b, d, h, m, n, p, and r. Caps are usually taught as pen lifts instead of retrace: B, D, M, N, P, and R. Finally, you can make words out of the smalls, but not the caps.”

Virginia Berninger, a UW educational psychology professor, who studied the effect of handwriting on the human brain, says that it is important to teach lowercase letters first because they are used more frequently in writing and are encountered more frequently in written text. Uppercase should only be taught once lowercase letters are legible and automatic. Teachers should also keep written work to a minimum until lowercase writing is functional.

Finally, Dr. Steve Graham, the Warner Professor in the Division of Leadership and Innovation in Teachers College who has studied how writing develops, and how to teach it effectively for over 40 years, confirms that it is best to teach lowercase because “it is more economical” to do so.

In conclusion, emphasizing the instruction of lowercase letters in early education offers numerous advantages. This approach aligns with efficiency and functionality, establishing a robust foundation for

effective writing skills. The evidence from both practical considerations and expert insights supports the prioritization of lowercase instruction for enhanced educational outcomes.

References

Berninger, V. W., & Wolf, B. J. (2009). Teaching students with dyslexia and dysgraphia: Lessons from teaching and science. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing Company.

Maria, Jason Santa. “How We Read.” A List Apart, 2014. Web. 15 Dec. 2016. Retrieved from http://alistapart.com/article/how-we-read

HANDWRITING HEROES

HANDWRITING HEROES